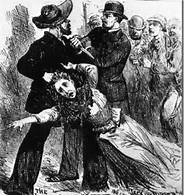

A cheery subject for you just before the Christmas holidays: beating your wife in Victorian England! Today’s guest post is by Melissa Black from Yesterday Enchanted.

Ever wondered where the term, ‘Rule of thumb’ came from? It derived from old British legal traditions which considered a husband the ruler of his wife. Once married a husband could be held legally liable for his wife’s conduct in early modern times and as such, it was a widely held belief a husband could strike his wife for ‘lawful correction’ or to ‘order and to rule her’. A famous judge Sir William Blackstone’s wrote an influential book in the eighteenth-century called Commentaries on the Law of England and stated, ‘For as the husband is to answer for his wife’s misbehaviour, the law thought it reasonable to intrust him with this power of restraining her, by domestic chastisement, in the same moderation that a man is allowed to correct his …children’.

In the nineteenth century, people were influenced by popular mythology of these ideas. Cartoons depicting a judge who had purportedly stated it was lawful for a husband to beat his wife provided the stick was no thicker than his thumb had appeared in the press in 1782, suggesting the question of the severity of a beating was ambiguous and one for the individual husband.

In the nineteenth century, people were influenced by popular mythology of these ideas. Cartoons depicting a judge who had purportedly stated it was lawful for a husband to beat his wife provided the stick was no thicker than his thumb had appeared in the press in 1782, suggesting the question of the severity of a beating was ambiguous and one for the individual husband.

Whilst there was actually no legal validation for this, there was continued widespread contemporary belief there had been legal significance attached to the rule of thumb, which some have claimed perhaps was a euphemism for no rule at all.

The upper classes did not condone violence, and considered the fights between working class husbands and wives, which would spill out onto the crowded streets of London, as one part of a generalized ‘savagery’ of the uncivilized masses. The Middle class considered working class males fundamentally primitive, with areas such as Liverpool docklands or Lancashire mining areas barely ‘civilized’ and whose masculine nature had not yet been properly disciplined.

In 1816 The Morning Post reported a ‘Daring Robbery’ which described two villains entering a shop of a Mr Moses Levy, upon whom they beat and threatened to murder, along with his wife. They then robbed the shop of various articles, during which time an accomplice stood outside the shop door and told passers-by whom heard the noise that it proceeded from Levy who was beating his wife! Needless to say, the assumption was the passer-by’s walked on!!

The law in Victorian England sanctioned a degree of physical force as male patriarchy was considered integral to a smooth running of society. Whilst women came to magistrates to charge their husbands with assaulting them, the courts at this time usually reserved judicial treatment for extreme cases of domestic violence involving death or extraordinary injury in the early nineteenth century. Lesser violence was considered disgraceful by the courts but not necessarily treated as criminal. There was also a persistent idea of wives being tolerant toward a degree of ‘rough usage’ by husbands, so the courts stressed violence didn’t represent for the poor what it would for higher classes, and hence required lesser treatment.

In a case of, ‘Breach of the peace’, a beaten wife stated upon questioning as to her complaint, ‘Complaint! What would I complain against him for! I have a right to complain of those that wouldn’t let him alone. I dare say I ain’t a bit better than him. At any rate, he is the father of my children, and he works for ‘em, and why should I stand a lick now and then, if he fancies it? God bless your Lordship and leave us to settle the business ourselves.’ The prosecutor then turned to the Lord Mayor and stated, ‘She’ll manage him better than we can, my Lord’ with the defendant permitted to go upon the assurance that he would never take a drop of gin again, except in the company of his wife! Whilst contemporary observations of living conditions amongst the poor poignantly explained this through material dependence, others felt women just accepted it as part of working class life.

In the latter half of the nineteenth-century however, domestic violence, or wife-beating as it was known in the Victorian era emerged as a serious social concern This era saw a rise in the standard of treatment towards women and new notions of ‘manly’ behaviour corresponding to the practice of a moral, rather than physical, control over wives. Middle class religious and secular venues pushed an Evangelical campaign promoting ideas of education and morality, and non-violence to society.

The everyday violence the British were used to such as state sanctioned whippings, hangings and brutal sports such as dog and cock-fighting were slowly being replaced by penal institutions and transportation to the colonies, and male aggressiveness once considered an integral part of English masculinity was promoted to become more law-abiding and self-disciplined, with the idea slights were avenged with self-restraint, prudence and forethought. These bourgeois or middle class values committed to a peaceful home and family life, and came to be considered the only way to live in Victorian England. Now more than ever it was assumed that men were in need of women to ‘elevate them and save their souls, as domestic and intimate ‘angles’. Queen Victoria herself nobly depicted her blissful, yet submissive status as a dutiful wife and mother, reinforcing the family as the defender of the social order, with any interference considered a threat to stability.

The everyday violence the British were used to such as state sanctioned whippings, hangings and brutal sports such as dog and cock-fighting were slowly being replaced by penal institutions and transportation to the colonies, and male aggressiveness once considered an integral part of English masculinity was promoted to become more law-abiding and self-disciplined, with the idea slights were avenged with self-restraint, prudence and forethought. These bourgeois or middle class values committed to a peaceful home and family life, and came to be considered the only way to live in Victorian England. Now more than ever it was assumed that men were in need of women to ‘elevate them and save their souls, as domestic and intimate ‘angles’. Queen Victoria herself nobly depicted her blissful, yet submissive status as a dutiful wife and mother, reinforcing the family as the defender of the social order, with any interference considered a threat to stability.

New law’s concerning recompense for women whom were severely mistreated by their husbands represented new outlooks toward domestic violence. In 1853 the Member for Lewes, a Mr Fitzroy, agitated against the manifestly inadequate penalties for aggravated assaults on women and children which resulted in the passing of the Aggravated Assault on Women and Children Act.

New law’s concerning recompense for women whom were severely mistreated by their husbands represented new outlooks toward domestic violence. In 1853 the Member for Lewes, a Mr Fitzroy, agitated against the manifestly inadequate penalties for aggravated assaults on women and children which resulted in the passing of the Aggravated Assault on Women and Children Act.

One middle-class reformer placing a ‘Warning to Wife-Beaters’ in the Leeds Intelligencer in response stated, ‘Among the signs of the times which cannot be looked upon as evidences of improvement, or proofs of any other description of ‘progress’ than the progress of barbarism, there is one which has latterly become of such frequent and increased occurrence, that it has forced itself upon the attention of our rulers, and obliged a reluctant legislature to interfere on behalf of a suffering and much abused class’. Whilst the passing of the 1853 Act was considered by one parliamentarian to ‘extend the same protection to defenceless women as they already extended to poodle dogs and donkeys’, magistrates with summary jurisdiction could now impose heavy fines on males under 14 with up to 6 months imprisonment, with or without hard labour.

By 1857, The Divorce and Matrimonial Clauses Act was passed under strong feminist pressure and ‘cruelty’ was included as grounds for divorce. Within the next few years the threshold of ‘reasonableness’ for such apprehension was lowered by a series of rulings. Whilst in reality the proceedings were expensive and only attainable to middle class women, whom to leave a husband had to prove adultery as well, the law in relation to marriage was now taking a leading role in the repression of violence. With the perception ‘wife-battering’ was as an index to the level of violence in society generally, alongside the idea it was threatening marriage as the normative state and the subsequent pressure for a husband to work, domestic violence was finally ‘brought out from the shadows’ and emerged as a social concern. One writer claimed ‘There is not….. any class in the world so subjected to brutal personal violence as English wives’.

Whilst these new notions of masculinity remained hotly contested in parliament and the courts, with one famous judge Edward Cox describing the ‘termagant’ wife who made the home a living a hell, it was the deviation from bourgeoisie norms and notions of marital relations parliamentarians were most concerned about. Subsequently, in 1878 an amendment to the Matrimonial Causes Act was passed. This gave magistrates and judges the power to grant a separation in court to a wife whose husband had been convicted of an aggravated assault, along with the custody of children under ten and weekly maintenance. This proved the first real escape route for battered wives and the conditions for real social change. The next quarter century saw new legislation in the form of The Married Women’s Property Acts of the 1870’, 1880s and 1890’s, each contributing to wives leaving their husbands through the ability to support themselves and her children by her own efforts.

References:

Doggett, M.E., ‘Marriage, Wife-Beating and the Law in Victorian England’, Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 1993.

May, M., ‘Violence in the Family: An Historical Perspective’, in J.P. Martin (ed.), Violence and the Family, John Wiley & Sons, 1978.

Tomes, N., ‘A “Torrent of Abuse”: Crimes of Violence between working-class men and women in London, 1840 – 1875’, Journal of Social History, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1978, pp. 328 – 345.

Hi! My name is Geerte, I'm a researcher of Nineteenth century history from the Netherlands. This blog is where I write about my favourite subject. Feel free to browse around!

Hi! My name is Geerte, I'm a researcher of Nineteenth century history from the Netherlands. This blog is where I write about my favourite subject. Feel free to browse around!

I am under the impression that the etymology of “rule of thumb” referred to in the title is something of an urban myth.

Snopes, the OED, and even Wikipedia provide examples of the idiom being used in the conventional sense as early as the 17th century…

Wow! This was a fascinating read. I don’t think I’m going to use this expression anymore. Year of the woman and all that…

This was an interesting read, I never knew “rule of thumb” came from a domestic matter. At least now a days it’s used to describe basic foundation principles or basic building blocks for a concept.

I have a question though, if wife beating was seen as the savagery of the lower classes, then how did the upper class or nobles deal with “a misconducting wife” per say? Surely the higher classed families would of had their internal disputes, so how did they handle it during this era?

The phrase “rule of thumb” is used very often in the English language today as a broadly accurate guide or principle, based on practice rather than theory, therefore it is quite interesting and appalling to learn that it had stemmed from domestic abuse. While the correlation between its current and previous usage is very faint, it definitely has one rethinking its use. This is mainly due to the fact that despite of the regulations, the laws, feminism and the evolution of masculinity, the domestic violence is still very much prevalent in areas where masculinity dominates. In addition to that, modern media such as movies and music still portrays women as tools for men as opposed to panthers.

I have to disagree with you on that. With the rise of feminism there’s been a shift in domestic abuse. Now it is the women abusing the men. And with laws and regulation in womens’ favor, there is no protection for men being abused by their wives or girl friends. A man who sums up the courage to speak out and say a woman is abusing him is laughed at and mocked, but women are instead considered brave, and rightly so too, but the same protection and assistance extended to women is not extended to men.

As far as modern media movies go, I don’t know what you’ve been watching, but I am personally sick of being bombarded by female lead dominated films, female hero films, “women empowerment” films. For the last 2 years the cinema was filled with “women in charge” films. It went from being enjoyable to being an annoyance.

As far as language goes, words and phrases do shift and evolve over time. So while rule of thumb had a disturbing origin, it’s present meaning is very favorable. I see no reason to rethink it’s use. It’s like people using knives as weapons, then 50 years later people use knives as culinary tools instead. (for the purpose of this weak example, I’m ignoring the fact that knives can still be used to kill people)

.

I have to disagree with you on that. With the rise of feminism there’s been a shift in domestic abuse. Now it is the women abusing the men. And with laws and regulation in womens’ favor, there is no protection for men being abused by their wives or girl friends. A man who sums up the courage to speak out and say a woman is abusing him is laughed at and mocked, but women are instead considered brave, and rightly so too, but the same protection and assistance extended to women is not extended to men.

As far as modern media movies go, I don’t know what you’ve been watching, but I am personally sick of being bombarded by female lead dominated films, female hero films, “women empowerment” films. For the last 2 years the cinema was filled with “women in charge” films. It went from being enjoyable to being an annoyance.

As far as language goes, words and phrases do shift and evolve over time. So while rule of thumb had a disturbing origin, it’s present meaning is very favorable. I see no reason to rethink it’s use. It’s like people using knives as weapons, then 50 years later people use knives as culinary tools instead. (for the purpose of this weak example, I’m ignoring the fact that knives can still be used to kill people)

Women are abusing men, but CERTAINLY not at a higher rate than men are women. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, “76% of intimate partner physical violence victims are female; 24% are male.” There’s definitely a social stigma against men who speak up against violence they’ve faced against women, but that’s no need to invalidate the experiences women all over the world have been facing for thousands of years at the hands of their husbands/boyfriends/partners.

On the topic of female-dominated films: if you don’t want to watch them, then don’t. Representation is a big deal for traditionally underrepresented minorities—women, people of color, LGBTQ+—but as someone who’s never had the issue finding someone in a movie who looks like them (or better yet, who they could project themselves onto and relate to), it can be difficult to understand. Men have never struggled to land roles as the leading heroes in films; women, however, have historically been the love interests.

It think it’s sad that a film depicting a woman rescuing a man (which is more common in real life than you might think, though maybe not from dragons) is depicted as “ground-breaking”, while a film depicting a man saving a woman is seen as, well, just another movie! It speaks volumes of how society has traditionally portrayed women in media.

Anyways, LOTS of the “female empowerment” movies (“Hidden Figures”, “I, Tonya”, etc.) are based on real-life women who accomplished great things, so why act as if their stories are an annoyance while male-led biopics continue to dominate (“Walt Before Disney”, “The Greatest Showman”, “Christopher Robin”) are an annoyance? Try and ask yourself why you’re upset with female-led films, because women everywhere have been watching male-led films since, well, the inception of film!

I have to agree and disagree with some of your statements. Yes women were at the short end of the stick for many centuries. But the decision of some women to abuse their male partners only shows them as being no better than the abusive men in the past. I cannot speak for worldwide figures, but in my country there is a much higher degree of women abusing men and embarrassing them in public. It’s quite revolting if you witness them. While I don’t intend to invalidate the wrongs of the past, I don’t believe that most families had abusive husbands or partners, but it makes sense to record the negative and not the positive, which is a lacking data set. How common were abusive partners in comparison to decent loving families? Was this an issue in one country and not another? There are studies saying that women in some indigenous tribes were well respected, in another tribe a woman can never be chief, but her opinion would still be heard. But in say India, women were treated worse than dogs for decades.

It is difficult for me to see the importance of film representation since I grew up knowing that it’s just a movie/fiction, someone’s creation to make money. So I never understand when people get emotional and attached to movies and actors etc i’ll admit that. My issue with the female lead films I’ve seen eg the new Ghostbusters, the women don’t act like say mature responsible people with a sense of humor, they act stupid, like the actors in a parody film. Proud Mary could of been much better. To me, it feels like movie makers are feeding off people’s wants for a “female lead” and producing poor quality films. It doesn’t feel like there’s a woman in a situation and following a character arc that people can learn from, it feels like a rushed story/weak actress sprinkled in special effects depending. I’ll agree with you that we’re accustomed to male led films, but even in that category there have been great films and crappy trash. But at the end of the day, that’s just how I feel about these films. It’s not that I hate women-in-films, but I dislike the feel that producers are just trying to gain crowds by showing a female on the front cover, but the quality of the film isn’t worth it. Sadly a movie’s synopsis doesn’t warn you of the film’s quality, so I don’t always have the option to safely avoid a silly film.

As to historical films, I don’t regard them as female empowerment if they are based on real events. To me it’s someone trying to show the world that this forgotten person, male or female, was involved in this event which we take for granted. Women have made many important contributions to humanity, especially in the fields of medicine and science, but their credit and fame were often stolen by their male superiors. So I fully support any film that says : hey, this is what really happened. Hidden figures was great, Greatest Showman was a rushed story soaked in flashing lights. (no pun intended).

PS I wish all men would treat women as love interests like in the older films. If they did, there’d probably be less if no violence against women. Spread the love.

Hi

I Will Provide 20.000 Backlinks From Blog Comments for 19thct.com,

By scrapebox blast to post blog comments to more than 400k blogs from where you will receive at least 20 000 live links.

– Use unlimited URLs

– Use unlimited keywords (anchor text)

– All languages supported

– Link report included

Boost your Google ranking, get more traffic and more sales!

IF YOU ARE INTERESTED

CONTACT US =>